| |

Prepared in collaboration with Noriyuki Murakami

Outline of Sections

|

Summary of Basic Science and Clinical Information for African Trypanosomiasis (PDF)

(Chapter 6 from: Parasitic Diseases 5th Ed.) |

Section 1 |

|

Section 2 |

|

Section 3 |

|

Section 4 |

|

4.1 |

|

4.1.1 |

|

4.1.2 |

|

4.1.3 |

|

4.2 |

|

4.2.1 |

|

4.2.2 |

|

Section 5 |

|

5.1 |

|

5.2 |

|

5.3 |

|

5.4 |

|

Section 6 |

|

6.1 |

|

6.2 |

|

6.3 |

|

6.4 |

|

6.5 |

|

Section 7 |

|

Section 8 |

|

12/24/05 |

|

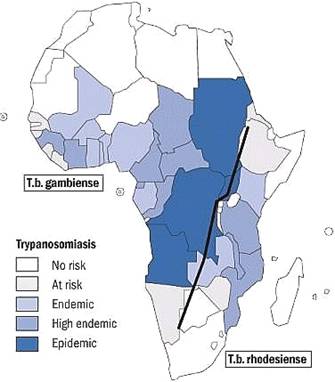

Sleeping sickness, also known as Human African Trypanosomiasis (HAT), is caused by Trypanosoma brucei rhodensiense in Eastern Africa and Trypanosoma brucei gambiense

in Western Africa . Both protozoan species are morphologically

indistinguishable, but have drastically different epidemiological

features. Several species of hematophagous glossina, commonly known as

tsetse flies, are the vectors of these related diseases, and are

responsible for cyclical transmission of the parasitic protozoan between

numerous vertebrate hosts. Both forms of sleeping sickness affect the

central nervous system. The term “sleeping sickness” is derived from the

West African form of trypanosomiasis, primarily because invasion of the

cerebrospinal fluid and brain after infection of the blood is often

delayed, resulting in symptoms of extreme fatigue that can last for

several years before the severe phase of the disease sets in; toxemia,

coma and death. In contrast, the typical East African form of

trypanosomiasis is characterized by rapid and acute development of the

disease, and untreated patients can die within weeks or months of

infection.

|

East & West African Sleeping Sickness

(Map provided by WHO) |

Although epidemics of sleeping

sickness were more rampant in the past, the most recent WHO estimates

put 60 million people at risk of HAT today with approximately 500,000

people currently with infections. The disease is discontinuously spread

over 9 million square kilometers and affects populations across 37

sub-Saharan countries. Animal trypanosomiasis, caused by a wider number

of trypanosome species and carried with higher prevalence by a greater

number of glossina species, is invariably the greater epidemic across

the African continent with dire economic consequences. In general,

trypanosome infections that threaten livestock are over 100 to 150-fold

higher in G. morsitans than the trypanosome infections that

cause human trypanosomiasis (Jordan 1976). Historically, the impact of

animal trypanosomiasis were so profound that it influenced the migration

routes of cattle-owning tribes into the continent who were forced to

avoid the G. morsitans “fly-belts” (Ford 1960), as well as the movements

of early European and Arab settlers into the continent who depended on

horses and oxen (McKelvey 1973).

Of the 31 species of glossina in

the African continent, eleven are important for transmitting the

infection to humans. Today, most efforts to reduce transmission of the

disease to humans and other vertebrate reservoirs focus on the control

of only these species. Clinical treatment of both early and late onset

sleeping sickness is limited and far from up-to-date, and thus cannot be

relied upon for controlling the spread of the infection during times of

epidemics. Therefore, understanding the ecological factors that

determine patterns of transmission to people, and those that play a role

in the re-emergence of the disease is vital to the design of new

effective programs to reduce the burden of disease in human populations.

This web site emphasizes the ecology of the tsetse vectors and also

documents some of the more useful control strategies to limit their

populations.

The earliest recorded account of sleeping sickness comes from upper Niger during the 14th

century in the historical writings of Ibn Khaldoun, who wrote about the

disease in his account of the history of North Africa . The next report

came from Guinea in 1734 (Atkins, 1978). In 1803, the diseases that

caused visible swollen lymph glands in West Africa came to be known as Winterbottom's sign,

after the description of the disease by Winterbottom. Such signs were

readily recognized by slave traders who avoided trading and buying

slaves who displayed those symptoms.

|

Sir David Bruce |

The earliest detection of

trypanosomes in human blood was in 1902, when R.M. Forde discovered what

was then thought to be filiaria in the blood of a steamboat captain who

had traveled extensively along the River Gambia. Similar discoveries of

filiaria-like organisms in the blood were made by J.H. Cook in East

Africa, but confusion arose as to how filiaria worms could cause such

varying clinical symptoms. It was J.E. Dutton who, during a visit to

Gambia, first correctly identified the parasite as a trypanosome and

subsequently named it Trypanosoma gambiense . In

1902, A. Castellani observed the presence of trypanosomes in

cerebrospinal fluid taken from a sleeping sickness patient, but it

wasn't until 1903 that D. Bruce correctly recognized that trypanosomes

were the causative agents of sleeping sickness transmitted to humans by

tsetse flies, and that “trypanosome fever” and “sleeping sickness” -

both thought to be different diseases at the time - were in fact the

same.

Morphologically indistinguishable from the West African species as well as the animal infecting species Trypanosoma brucei brucei, Trypanosoma brucei rhodensiense was first discovered in Zambia by J.W.W. Stephens and H.B. Fantham in 1910. By 1926, T.b. rhodensiense

could be found along the fly-belt between Tabora and Kigoma, Tanzania .

The difficulties in identifying this virulent form of sleeping sickness

lead to uncertainties today regarding the evolution and progression of T.b. rhodensiense through the continent, although it is generally agreed upon that it originated from the West African form.

The earliest recorded major

epidemics of sleeping sickness took place in Uganda and Congo between

1896 and 1908, where roughly 500,000 people were estimated to have died

in the Congo Basin, and approximately 300,000 died in Busoga, Uganda .

With the Rift Valley transecting the country, Uganda is in the

precarious position of having foci of both forms of diseases which

resulted in two other major epidemics of sleeping sickness - one in the

late 1940's and another in 1980. Throughout West Africa, smaller

epidemics of sleeping sickness rapidly spread from Senegal to Cameroon

during the 1920's, and died down by the late 1940's.

African trypanosomes are extracellular organisms, both in the mammalian and insect host. T. b. gambiense and T. b. rhodesiense are morphologically indistinguishable, measuring 25-40 µ m

in length. Infection in the human host begins when the infective stage,

known as the metacyclic stage, is injected intradermally by the tsetse

fly. The organisms rapidly transform into blood-stage trypomastigotes

(long, slender forms), and divide by binary fission in the interstitial

spaces at the site of the bite wound. The buildup of metabolic wastes

and cell debris leads to the formation of a chancre  . .

Trypanosomes have a single specialized mitochondrion called a kinetoplast mitochondrion. One

of its unusual features is that all of the DNA of the mitochondrion,

which can be up to 25% of the total cell DNA, is localized in the

kinetoplast, adjacent to the flagellar pocket. Kinetoplast DNA or kDNA

exists in two forms: mini-circles and maxi-circles. Mini-circle DNA

encodes guide RNAs that direct extensive editing of RNA transcripts

post-transcriptionally. Maxi-circle DNA contains sequences that, when

edited, direct translation of typically mitochondrially-encoded

proteins.

In the vertebrate host,

trypanosomes depend entirely upon glucose for energy and are highly

aerobic, despite the fact that the kinetoplast-mitochondrion completely

lacks cytochromes. Instead, mitochondrial oxygen consumption is based on

an alternative oxidase that does not produce ATP. When in the insect

vector, the parasite develops a conventional cytochrome chain and TCA

cycle.

|

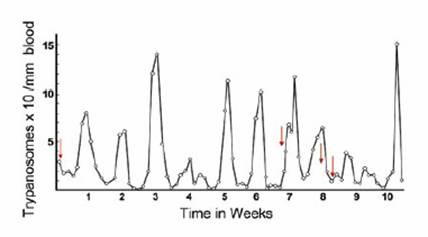

The surface of the trypanosome has numerous membrane-associated transport proteins for

obtaining nucleic acid bases, glucose, and other small molecular weight

nutrients. None of these proteins react well with antibodies, because

although they lie in exposed regions of membrane, they are shielded by

allosteric interference provided by the variant surface glycoprotein

(VSG) coat proteins. This flagellated stage enters the bloodstream

through the lymphatics and divides further, producing a patent

parasitemia. The number of parasites in the blood is generally so low

that diagnosis by microscopic examination is often negative. At some

point, trypanosomes enter the central nervous system, with serious

pathological consequences for humans. Some parasites transform into the

non-dividing short, stumpy form  , which has a biochemistry similar to those of the long, slender form and the form found in the insect vector. , which has a biochemistry similar to those of the long, slender form and the form found in the insect vector.

The tsetse fly becomes infected

by ingesting a blood meal from an infected host. These short, stumpy

forms are pre-adapted to the vector, having a well developed

mitochondrion with a partial TCA cycle. In the insect vector, the

trypanosomes develop into procyclic trypomastigotes  in the midgut of the fly, and continue to divide for approximately 10

days. Here they gain a fully functional cytochrome system and TCA cycle.

When the division cycles are completed, the organisms migrate to the

salivary glands, and transform into epimastigotes. These forms, in turn,

divide and transform further into metacyclic trypanosomes, the

infective stage for humans and reservoir hosts. The cycle in the insect

takes 25-50 days, depending upon the species of the fly, the strain of

the trypanosome, and the ambient temperature. If tsetse flies ingest

more than one strain of trypanosome, there is the possibility of genetic

exchange between the two strains, generating an increase in genetic

diversity in an organism that may not have a sexual cycle.

in the midgut of the fly, and continue to divide for approximately 10

days. Here they gain a fully functional cytochrome system and TCA cycle.

When the division cycles are completed, the organisms migrate to the

salivary glands, and transform into epimastigotes. These forms, in turn,

divide and transform further into metacyclic trypanosomes, the

infective stage for humans and reservoir hosts. The cycle in the insect

takes 25-50 days, depending upon the species of the fly, the strain of

the trypanosome, and the ambient temperature. If tsetse flies ingest

more than one strain of trypanosome, there is the possibility of genetic

exchange between the two strains, generating an increase in genetic

diversity in an organism that may not have a sexual cycle.

Flies can remain infected for

life (2-3 months). Tsetse flies inject over 40,000 metacyclic

trypanosomes when they take a blood meal. The minimum infective dose for

most hosts is 300-500 organisms, although experimental animals have

been infected with a single organism. Infection can also be acquired by

eating raw meat from an infected animal. In East Africa, this mode of transmission may be important in maintaining the cycle in some reservoir hosts.

4 |

Medical Ecology of Sleeping Sickness

Part I: The Vector |

|

4.1 |

Classification and Distribution |

|

|

| |

There are 31 species and subspecies of tsetse flies under the genus Glossina, family Glossinidae, and order Diptera.

Tsetse flies are largely classified into three subgenera based on

morphological differences in the structure of the genitalia: Morsitans (Glossina), Palpalis (Nemorhina), and Fusca (Austenina)

groups. Although the tsetse flies can be found over some 9 million

squared kilometers of the African continent, presence of glossina

populations throughout the continent are far from continuous. In

general, the Sahara and Somali Deserts limit the populations in the

north, extending across the entire continent from Senegal in the west to

southern Somalia in the east. Tsetse populations are denser in West and

Central Africa, and are found more sporadically to the East and down to

the borders of the Kalahari and Namibian Deserts in Southern Africa .

Although tsetse fly habitats may vary considerably, climate and altitude

- through their direct effects on vegetation, rainfall, and temperature

- are still the primary determinants for proliferation. Unlike other

insects, there are no seasonal interruptions in the life cycles of

tsetse flies. However both adult longevity and puparial duration are

related to temperature, and a significant seasonal decline in tsetse

populations is normal, particularly in savannah habitats during the dry

season. The 3 groups of tsetse flies are generally adapted to different

habitats and ecozones.

Brief summary of ecological zones in Africa (adapted from Jahnke, 1982)

| Characteristics |

Ecological Zones |

| |

Arid |

Semi-arid |

Sub-humid |

Humid |

Highlands |

Area (1000km2) |

8327 |

4050 |

4858 |

4137 |

990 |

Rainfall (mm) |

<500 |

500-1000 |

1000-1500 |

>1500 |

Variable |

Moisture Index |

36 |

20 |

0-20 |

0 |

Variable |

Growing Days |

<90 |

90-180 |

180-240 |

>240 |

Variable |

Area of Tsetse (1000km2) |

438 |

2036 |

3298 |

3741 |

195 |

Area of Tsetse % |

4.2 |

50.3 |

68.2 |

89.7 |

1.9 |

Predominant Tsetse Group |

Morsitans |

Morsitas

Palpalis |

Palpalis

Fusca |

Fusca

Palpalis |

None |

4.1.1 |

Habitat and Distribution of the Morsitans Group |

|

There are seven species that fall

into the morsitans group. All are potential vectors of both human and

animal trypanosomiasis. The three Glossina morsitans

subspecies are exceptionally good vectors of trypanosomes. All species

within this group inhabit the savanna woodlands that surround the two

major blocks of lowland rain forests in Africa . The distributions of

tsetse flies in this group closely follow the distributions of wild

animals and water sources. In the wetter areas the flies are observed to

roam more widely over the woodland, but in drier areas their movements

are restricted to mesophytic vegetation of the watercourses.

In Eastern and Southern Africa where Glossina morsitans morsitans is the primary vector for human and animal trypanosomiasis, the "miombo" woodlands (Brachystegia-Julbernardia) that extend from Mozambique to Tanzania, as well as the "mopane" woodlands (Colophospermum mopane) in Zambia and Zimbabwe are the typical habitats. The other subspecies Glossina morsitans centralis

dominate northwards from Botswana and Angola into Southern Uganda,

closer inland towards the lowland forests but also occurring in miombo

vegetation. Glossina morsitans submorsitans have an east to

west distribution from Ethiopia to Senegal in ‘doka' woodlands where the

vegetation is dominated by Isoberlinia species, and can be sporadically

found to occur in the southern Guinea savanna vegetation zone as well

in the drier Sudan zone.

Glossina swynnertoni is restricted to a small area between northern Tanzania (Serengeti) and Southern Kenya (Masai Mara) where the Acacia-Commiphora vegetation can be found, along with an abundance of wild life. Glossina longipalpis and Glossina pallidipes

both have a much wider range of possible habitats displaying

versatility by existing in different vegetation types. Glossina

longipalpis occurs mainly in the narrow savannah belt just north of the

rain forest in West Africa, from Guinea to Cameroon . Much of the

savannah is derived from human destruction of the climax forest

vegetation, and as a result is spreading southwards. The highly mobile

Glossina pallidipes occurs in East Africa from Mozambique to Ethiopia

over a relatively wide range of climatic and vegetation conditions.

Finally, Glossina austeni occupy secondary scrub, thicket and

islands of forest along the East African coast from Mozambique to

Somalia. However, its distribution is discontinuous, rarely being found

at altitudes over 200 meters or more than 250 km inland from the coast.

4.1.2 |

Habitat and Distribution of the Palpalis Group |

|

see distribution of palpalis group in Africa

Of the nine species in the palpalis subgenera, the five palpalis and fuscipes subspecies are vectors of both human and animal trypanosomiasis. Although flies in this group are continuously found in the lowland rainforests,

some are known to extend out to the savannah regions particularly along

rivers and streams. The habitat of the palpalis flies occur mainly in

the drainage systems leading to the Atlantic or the Mediterranean Ocean,

extending from the wet mangrove

and rain forests along the coastal regions of West Africa to the drier

savannah areas just north of the rain forests. The flies in the palpalis

group are less tolerant to the wide range of climatic conditions of the

savannah belt, and are therefore restricted to the ecoclimate of the

watercourses from where they derive their label as the ‘riverine

species'. Many of the palpalis species, such as the Glossina palpalis palpalis

in Côte d'Ivoire, prefer peri-domestic conditions and have been

observed to maintain close association with villages (Baldry, 1980).

Similarly, it is thought that the advancement of Glossina tachinoides

into Eastern Côte d'Ivoire and Togo have been attributed to the intense

agricultural development and the rapid human population growth around

the plantations (Hendrickx and Napala, 1997). In general, most of the

flies in this group are less suited to desiccating conditions, and

therefore survive in thick riverine forests with enough shelter from

winds and heat. This is especially the case for the three fuscipes

subspecies which are confined to hygrophytic habitats, rarely far from

open water lacustrine or riverine habitats. Glossina tachinoides,

although typically a riverine species, were found in northern Nigeria

to extend into human-inhabited savanna woodlands during the wet season,

also displaying strong adaptations to peridomestic habitats (Kuzoe et

al., 1985).

4.1.3 |

Habitat and Distribution of the Fusca Group |

|

see distribution of fusca group in Africa

With the exception of Glossina brevipalpis and Glossina longipennis,

all the tsetse flies in the fusca group are found in West African

forests. None of the species in the fusca group are vectors of human

trypanosomiasis, however both Glossina fusca and Glossina medicorum are efficient vectors of trypanosomes to livestock (mainly Trypanosoma vivax),

causing considerable economic burden. Distributions of the fusca group

tsetse depend primarily on forest vegetation and climatic factors. With

the exception of G. longipennis, most fusca group species inhabit moist,

evergreen habitats either in riverine forests within savannas (such as Glossina medicorum) or in dense and wet rain forests (Glossina tabaniformis and Glossina nigrofusca).

In stark contrast to the rest, the G. longipennis species lives in one

of the driest habitats inhabited by tsetse flies. Due to its pupal

adaptation to dry conditions, its primary habitat - consisting of dry

deciduous acacia bush – are discontinuously spread throughout East

Africa (Glasgow, 1963).

4.2 |

Susceptibility Factors |

|

The intrinsic vectorial capacity

of a tsetse fly refers to the intrinsic capability of a fly to develop a

metacyclic infection (Le Ray, 1989). In general, infection rates of the

three salivarian trypanosome subgenera (Dutonella, Nannomonas, and

Trypanozoon) are usually low in populations of tsetse, with infections

rates determined by the parasite, the host, the vector, and the

environment (Jordan, 1974). Trypanosoma infection rates in tsetse flies

vary greatly from species to species, with T. vivax ranking the highest and T. brucei species ranking the lowest.

Factors Influencing Trypanosome Infection Rates in Tsetse

(adapted from Jordan 1974 and Molyneux 1980)

| Endogenous Factors (Vector) |

Parasite Factors |

| Tsetse species |

Parasite numbers available to tsetse |

| Sex |

Parasite species and its infectivity to tsetse |

| Age at infective feed |

Subspecies/strain |

| Age structure of tsetse population |

|

| Genetic differences (variations within species) |

|

| Behavior (host preferences) |

|

Concurrent infections (virus, bacteria, fungi) |

|

Interactions between lectins and Rickettsia-like organisms |

|

Physiological and biochemical state |

|

| |

|

| Ecological Factors (Environment) |

Host Factors |

| Climatic factors |

Susceptibility |

| Availability of infected hosts |

Immune state of host |

| Hosts available for subsequent feed |

Behavior and attractiveness to tsetse |

Tsetse fly species differ in

their ability to develop infections, as discussed earlier. Female tsetse

flies usually have higher infection rates than males, partially because

females live longer than males and therefore have a higher probability

of infection. However is has not yet been determined whether the sex of a

fly influences the infection rate (Kazadi 1991, Mihok, 1992). Within

species it is found that infection rates vary greatly depending on

individual host factors. It has also been shown that susceptibility of

flies to infection with T. brucei is also due to a maternally inherited

characteristic, associated with the presence of intracellular

rickettsia-like organisms (RLOs). Tsetse flies carrying RLOs in the

midgut were found to be six times more likely to be infected with

trypanosomes than those without (Maudlin et al., 1990). Within any given

species, individuals and sexes of the same species respond differently

to infection suggesting some involvement of the genetic differences

(Jordan, 1974).

4.2.1 |

Behavioral Ecology of the Vector: Mating |

|

The mating behavior of tsetse

flies have received much attention because of the development of the

Sterile Insect Technique (SIT) for tsetse fly control. The existence of

tsetse flies at low densities in certain areas (as low as 40 per km2)

suggest highly specific mating mechanisms involving visual and

olfactory responses (Glasgow, 1963). Female tsetse flies only need to

mate once in their lifetime, but multiple matings have been known to

occur occasionally (Jaenson, 1980). Cross-mating is possible in areas

where habitats of different species overlap, however male hybrids are

infertile (Jackson, 1950). Mating of female is mostly confined to early

life with mean duration of mating declining by age. Most female flies

are successfully inseminated even at very low population densities,

usually during their first blood meal right after emergence from the

pupal stage (Teesdale, 1940).

4.2.2 |

Behavioral Ecology of the Vector: Host Feeding |

|

Tsetse flies use visual and

olfactory characteristics to recognize potential hosts before initiating

host-oriented responses. There are a series of behavioral responses

involved in the process of obtaining a bloodmeal. Host-seeking behaviors

are influenced by endogenous and exogenous factors. Endogenous factors

include circadian rhythm of activity level of starvation, age, sex and

pregnancy status of the fly (Brady, 1972). Exogenous factors include

temperature, vapor pressure, visual and olfactory stimuli, and

mechanical stimulation (Huyton and Brady, 1975). There are four stages

of host-locating behavior as described by Wilemse and Takken (1994):

Ranging

Flying in search of a host in the absence of an external cue.

Activation

Change in behavior caused by perception of external stimulus

Orientation

Upwind anemotaxis in response to complex chemical and visual stimuli directing the insect to the host

Landing

Generally, the tsetse fly will

detect an odour plume upwind until it visually recognizes the host.

After landing on the host, heat stimulation cause a probing and feeding

response. It was found that feeding activity for the morsitans group

tsetse were highest during the early morning and the late afternoon due a

combination of both external temperatures (20%) and circadian rhythm

(80%) (Brady and Crump, 1978).

It is thought that tsetse flies

originally fed on reptiles living in forests and later became adapted to

feeding on mammals. Adaptations to feeding on warthogs are thought to

be one of the pathways by which tsetse flies entered the savanna

ecosystems, subsequently evolving as the separate morsitans subgenus

(Ford, 1970). Most of our knowledge about species specific host

preferences is derived from blood meal analyses of captured flies.

Summary of main hosts of tsetse determined from analysis of bloodmeals (adapted from Moloo, 1993)

Host |

Morsitans Group |

Palpalis Group |

Fusca Group |

Domestic animals including human |

Human |

3.6 |

13.00(3) |

0.46 |

Cattle |

3.56 |

4.2 |

2.38 |

Sheep and Goats |

0.26 |

0.4 |

0.2 |

Donkey |

0.02 |

0.05 |

0.02 |

Dogs |

0.15 |

0.26 |

0.02 |

Domestic Pigs |

0.03 |

14.00(2) |

0.17 |

|

|

|

|

|

Sylvatic hosts |

Bushpig |

5.60 |

2.20 |

28.0(1) |

Warthog |

31.60(1) |

1.65 |

0.37 |

Total Suidae Total Suidae

|

45.36 |

18.50 |

33.1 |

|

|

|

|

Bushbuck |

10.18(2) |

25.12(1) |

11.2(2) |

Buffalo |

7.50(3) |

0.90 |

7.59(3) |

Kudu |

5.37 |

|

|

Total Bovidae Total Bovidae

|

43.22 |

45.50 |

28.1 |

|

|

|

|

Monitor Lizard |

0.036 |

6.02 |

0.05 |

Hippopotamus |

|

4.04 |

15.84* |

Rhinocerus |

|

|

14.20* |

Numbers in parentheses show host ranking in order of importance for each subgenera.

* Ranking for anomalous species G. brevipalpis and G. longipennis

|

4.3 |

Life Cycle of the Vector |

|

Unlike most insect species

(r-strategists) that produce large quantities of eggs, fertilized female

tsetse flies (k-strategists) “give birth” to one larva. A typical

female tsetse fly will produce one full grown larva approximately every

9-10 days depending on temperature and humidity. A single egg will hatch

and develop to a third-stage larva in the uterus of the female fly,

where it is nurtured and supplied with nutrients. This reproductive

process is known as adenotrophic viviparity . This form of

reproduction ensures the higher degree of survival of each offspring,

but is also the reason why reproductive rates are considerably low in

tsetse fly populations. In laboratory colonies, a single adult female

can produce up to 12 offspring this way, however in the wild the number

is speculated to be lower (Leak, 1999). Larviposition takes place when

the third-instar larva is deposited onto a suitable site, usually soil

or sand depending on the species, and the larva burrows down to its

optimum depth to become a pupa. Usually an adult fly will emerge after

the puparial period which varies according to temperature but on average

is around 30 days at 24°C (Leak, 1999). Longevity of the adult fly

varies greatly according to seasonal factors. For the general tsetse

population to increase, it is critical that the average female lifespan

exceed 36 days. During optimal conditions, female flies can live as long

as 3 months, producing as much 10 offspring during her lifetime

(Jordan, 1986).

Many population control methods

in the past have been successful because tsetse populations are far more

vulnerable to disruptions in life cycles than insects that are

r-strategists, such as mosquitoes. When both larval and adult mortality

rates are artificially increased through control methods such as fly

traps, insecticide spraying, and sterile insect techniques, the

reduction in reproductive rate is profound.

5 |

Medical Ecology of Sleeping Sickness

Part II: The Human |

|

see WHO annually reported cases of sleeping sickness by African countries

Although epidemics as large as

the ones in Uganda at the turn of the century have not been repeated,

there is much concern over the re-emergence and increase in the number

of sleeping sickness cases being reported every year in Africa. In 1994,

there were an estimated 150,000 cases in Congo, with prevalences as

high as 70% in some villages (Cattand, 1994). Despite the WHO projection

of 60 million people at risk in Africa, only a fraction of the

population at risk is currently under surveillance, and relatively few

cases are accurately diagnosed annually (Knudsen and Slooff, 1992).

Although sleeping sickness was largely under control during the 1960s,

recent epidemics have been strongly associated with political and civil

unrest in West and Central Africa resulting in mass movement of

populations into areas formerly uninhabited by humans.

5.1 |

Epidemiology of West African Sleeping Sickness |

|

West African sleeping sickness is

typically a chronic disease, making it a difficult disease to diagnose

in the field. Low levels of trypanosomes in circulating blood make it

difficult to detect the presence of parasites in blood smears, requiring

more sophisticated means of detecting trypanosomes such as with the use

of miniature anion-exchange / centrifugation (mAEC) technique. In

comparison to the East African form, T. b. gambiense has a

longer evolutionary history with humans, having successfully adapted to

establishing infections in human hosts without manifesting severe

symptoms. Astonishingly, infection rates of T. b. gambiense in wild glossina populations are as low 0.1%, even in areas with an epidemic of sleeping sickness (Jordan, 1986).

Vectors of the West African

sleeping sickness are species of the palpalis group, most of which are

in close contact with humans. Several different reservoirs for T. b. gambiense

have been identified, strongly suggesting that the persistence of

sleeping sickness in human populations may be maintained by other

animals, such as the African domestic pig (Watson, 1962; Gibson et al.,

1978;, Mehlitz et al., 1982). However, T. b. gambiense has not

been observed or proven experimentally to reach significantly

infectious levels of parasitemia in other reservoir hosts. Although it

is widely accepted that the human-to-fly contact is the main route of

transmission, some suggest a minor cycle involving an animal reservoir

may help explain the re-emergence and persistence of the disease in West

Africa (Noireau et al,. 1989).

The epidemiology of T. b. gambiense

sleeping sickness is far from being fully understood. Despite the low

levels of parasitemia in humans, the disease has successfully

established endemicity in many regions of West Africa . It has also long

been observed that the incidence of disease is not related to the

density of the glossina populations, and that epidemics often occur in

areas where the density of the vector is low (Jordan, 1986). In Nigeria,

sleeping sickness occured in the north where the distribution of G. p. palpalis and G. tachinoides

were scarce and restricted to vegetation close to watercourses during

the dry season (Edeghere et al., 1989). In Southern Nigeria, the same

species of tsetse flies are found in abundance due to favorable climatic

conditions, yet cases of sleeping sickness have never been observed. It

is thought that the nature of the human-fly contact is of particular

importance in the transmission of T. b. gambiense and the

distribution of the disease, and that human-fly contacts can be

classified as “personal” or “impersonal” depending on the ecological

circumstances of the interaction (Nash and Page, 1953). “Personal”

contact refers to situations where fly movements are restricted to areas

where exposure to humans are frequent, such as a watering hole or a

stream, and single tsetse fly can have multiple opportunities to feed on

humans. “Impersonal” contact occurs when fly movements are less

restricted, and where repeated contacts are not likely. In general,

ecological isolation of tsetse flies in the vicinity of human

populations lead to increased “personal” contact. Climatic stress, lack

of natural hosts where humans have destroyed wild animals close to

villages, or clearing vegetation for cultivation are all examples of

restrict movements of palpalis group vectors.

5.2 |

Epidemiology of East African Sleeping Sickness |

|

East African sleeping sickness

differs from West African sleeping sickness in both its epidemiology as

well as its clinical manifestations in mammalian hosts (Baker, 1974).

The clinical symptoms of East African sleeping sickness are more severe,

and the onset of the disease is rapid. In contrast to T. b. gambiense, T. b. rhodensiense occurs with higher levels of parasitemia in ungulates, and humans are the adventitious hosts. The vectors of T. b. rhodensiense are the G. mositans subspecies, G. pallidipes and G. swnnertoni species from the morsitans group, and on lesser occasions the peridomestic vectors from the palpalis group, G. fuscipes and G. tachinoides .

Sporadic cases usually arise from among those in the population whose

activities bring them into contact with the savannah woodland habitats

of the morsitans group. Although the vectors normally feed on game

animals, under extreme situations where “personal” contact is increased

due to social and/or environmental factors, a human-fly-human

transmission cycle may ensue resulting in an outbreak. Droughts and

political turmoil are known to increase the number of cases when entire

communities relocate to hitherto unoccupied areas in search of safety or

fertile lands and water (Molyneaux and Ashford, 1983).

5.3 |

Clinical Features and Disease Onset |

|

The clinical manifestations of

both forms of sleeping sickness are usually quite different, but can be

easily confused because of the variability of symptoms and length of

time until onset depends heavily on host characteristics (Molyneaux and

Ashford, 1983). The chancre, a leathery swelling at the site of the

bite, is usually the first symptom of the disease, primarily for T. b. rhodensiense. Within weeks, those with opportunistic levels of infection with T. b. rhodensiense start to experience irregular intermittent fevers associated with the waves of parasitaemia that are characteristic of T. b. rhodensiense infections. For T. b. gambiense,

lymphoadenopathy occurs more frequently. Oedema of the face is another

frequent sign of infection, and anemia may be present, particularly in T. b. rhodensiense.

There are two stages to sleeping

sickness; the early stage refers to the hemolymphatic infection, and the

late stage refers to infection of the CNS. The development of late

stage sleeping sickness may not occur for decades in West African

sleeping sickness, and a patient may only suffer mildly from fatigue due

to the occasional rises of parasites in the blood. However, East

African sleeping sickness is far more virulent, and can develop into

late stage sleeping sickness within weeks. Although symptoms and signs

associated with nervous system involvement are varied for both East and

West African sleeping sickness, advanced disease epileptic attacks,

maniacal behavior, somnolence and coma are some typical late stage

symptoms (Dumas and Bisser, 1999). Both treatment options and survival

rates are drastically reduced once the trypanosomes infect the CNS.

Today, there are only a handful

of active drugs available for treatment of human African

trypanosomiasis. No significant development has been made over the last 2

decades. The current line of treatment is problematic for many reasons:

firstly, the drugs are harmfully toxic requiring extensive

hospitalization. Secondly, regular follow-ups to check for relapse is

essential but difficult in many of the areas where sleeping sickness is

endemic.

Summary of drugs available for treatment of human African trypanosomiasis

(adapted from Bouteille et al,. 2003)

| Drug |

Marketed |

Specgtrum of Activity |

Stage of disease |

Suramin

(Germanin) |

1922 |

T. b. rhodensiense |

Stage 1 |

Pentamidine

(Pentacarinat) |

1937 |

T. b. gambiense |

Stage 1 |

Melarsoprol

(Arsobal) |

1949 |

T. b. gambiense

T. b. rhodensiense

|

Stage 1 & 2

Stage 1 & 2 |

Eflormithine

(Orindyl) |

1981 |

T. b. gambiense |

Stage 1 & 2 |

Treatment of the hemolymphatic stage is based on pentamidine and suramine . Melarsoprol,

an arsenic compound, is the only treatment option available for late

stage sleeping sickness because of its ability to penetrate the

blood-brain barrier. Unfortunately, even when administered under careful

medical attention, the treatment has a mortality rate as high as 12 %

(Apted, 1957). Eflornithine is effective against both stages of T.b gambiense infection, but not against T. b rhodensiense

(Iten et al., 1995). Although the most recent and effective drug

against sleeping sickness, it is not widely available, difficult to

administer, and costly for use under African health care conditions

(Bouteille et al., 2003) So far, only 2000 patients in therapeutic

trials have been treated with eflornithine.

Use of pentamidine as a form of mass

chemoprophylaxis has proven to be an effective form of prevention and

control in endemic foci of T. b. gambiense.

6 |

Medical Ecology of Sleeping Sickness

Part III: Prevention and Control |

|

In the absence of a vaccine for

trypanosomosis and with the looming threat of further trypanocidal drug

resistance, the most theoretically desirable means of controlling the

disease is through controlling the vector population (Leak, 1999).

Although complete eradication of the vector is impossible, the most

successful attempts at controlling tsetse flies are likely to be at the

extreme limits for survival of the fly, where both the density of the

fly is low and “personal” contact with humans may be highest (Rogers,

1979).

|

| |

There are several different

control techniques available today, but the use of chemicals in

controlling tsetse populations is still the most common method. In

brief, whether aerial or from the ground, residual insecticides such as

organochlorines (DDT, Dieldrin, Endosulfan), pyrethroids (deltamethrin,

permethrin, and alphamethrin), and avermectins (ivermectin) are used to

target areas where human-to-fly contact are likely. Pyrethroids are

preferred because they are rapidly degraded in soil and are

environmentally safe, unlike organochlorines, carbamates and

organophosphates that bioaccumulate in the food chain and are highly

toxic to mammals and other vertebrates. Despite being effective, the use

of organochlorines and organophosphates are now banned for widespread

outdoor spraying. Susceptibility to insecticides varies from one species

to another, and between the different classes of species (Leak, 1999).

The most common form of administering insecticides is through the use of

pressurized knapsacks. Over 200,000 km2 of tsetse-infested

land has been cleared by ground-spraying in West Africa, mainly in

Nigeria, and proved to be successful and cost-effective (Barrett, 1997).

Although the process is highly labor intensive and limited in

geographical scope, the spraying is administered discriminatively to day

and night resting sites during the dry season and are much more

effective than indiscriminate spraying from the air or from vehicles.

|

| |

Traps and targets are mechanical

devices used to kill or weaken tsetse flies through insecticides or

various trapping methods. The use of traps and targets to control tsetse

populations have been successful primarily because tsetse flies are

k-strategists with a low rate of reproduction, and require very little

sustained mortality pressure to bring about a reduction in population or

even eradication from an area (Weidhaas and Haile, 1978). Haargrove

(1988) estimated that an additional mortality of 4% per day imposed on

female flies was enough to cause extinction, in the absence of

immigration. The traps and targets attract tsetse flies by taking

advantage of their primary host-seeking behaviors, visual and olfactory

stimulation. The developments of potent attractants in the last 20 years

as well as the production of second-generation synthetic pyrethroid

insecticides are making this form of control technique highly successful

(Wall and Langely, 1991).

There are many prototypes of

traps and targets customized to attract as many tsetse flies as possible

in different environments, with a strong emphasis on designs that are

easy to duplicate and maintain locally. Although most traps are strongly

reliant on chemical attractants and insecticides, some have recently

been designed to attract tsetse flies based on visual stimulation alone

and to kill tsetse flies through a trapping mechanism (NGU and NG2B

traps). Although these traps may not be as efficient in attracting and

killing tsetse flies, they are far more affordable and feasible to

implement in resource poor settings. Such traps were used to

successfully suppress the tsetse fly populations in Nguruman, Kenya .

With the Maasai community involved, 190 homemade NG2B traps were

deployed over 100 km2, and a 98-99% G. pallidipes reduction was achieved over a 10 month period, and the reinvasion was kept relatively low during the rainy season (Dransfield et al,

1990). Targets and traps are usually deployed in and around areas where

human-fly contacts are greatest, such as streams frequented by

villagers, or fringes of cultivated fields. All aspects of these targets

and traps, from its design and color to their strategic placement, are

reliant on understanding the biology and behavioral ecology of the

various tsetse fly species.

Exploiting the knowledge that

tsetse flies concentrated in certain areas lead to numerous

bush-clearing projects all over West and East Africa to drastically

alter and maintain the area unsuitable for tsetse fly habitation.

Discriminative bush-clearing was used in Uganda to control for G.m. centralis

by clearing taller Acacia trees in the Ankole district (Harley and

Pilson, 1961). In Tanzania, between 1923 and 1930, bush-clearing methods

were also widely employed to stop the spread of sleeping sickness

epidemic in Maswa district, where G. swynnertoni was prevalent

(Leak, 1999). Similar tactics were used in Ghana to control sleeping

sickness around villages were human-fly contacts were high (Morris,

1949). Despite the apparent success of these methods, it is widely

accepted that bush-clearing is unsuitable as a long term control measure

due to the expense and speed of reinvasion, as well as the

environmental damage it causes through soil erosion, decreased soil

fertility, and its adverse effects on water supplies.

6.4 |

Sterile Insect Technique |

|

One of the more modern methods of

non-insecticidal control is the Sterile Insect Technique (SIT) which

was first considered as a means to control tsetse by Simpson in 1958.

This technique relies on the mating of wild females with sterile male

flies. Physiologically, female tsetse flies are only required to mate

once to store sperm in its spermathecae in sufficient quantity such that

fertilization can occur over its entire reproductive life. Mating with a

sterile male would thus result in no offspring. However, SIT was

considered to be impractical for control of high-density tsetse

populations above 1000 males per square mile due to the large number of

sterilized males that would be required. For SIT to be effective, it has

been estimated that 10% of the females in the population need to be

inseminated, and in order to achieve that, the number of sterile males

released must constitute 80% of the male population (Rogers and

Randolph, 1985).

Sterilization of male tsetse flies can be carried out by

Irradiation

Gamma rays, Beta rays

Chemosterilization

Bisazir, Metepa, Tepa, Apholates, Phytosterols

Physiological sterilization

Pyriproxyfen, Sulphaqunizaline, Chlordimeform

In 1994, an eradication program

conducted in Zanzibar by the authorities and the International Atomic

Energy Agency (IAEA) used a combination of insecticide-impregnated traps

and SIT to completely eradicate the entire tsetse population of

Zanzibar by 1996 (IAEA, 1997). Over 7.8 million gamma irradiated sterile

male G. austeni flies were released over the island with a

ratio of 50:1 sterilized males to wild males. This campaign may have

been successful in part because there is virtually no immigration of

tsetse flies into the island.

6.5 |

The Future of Sleeping Sickness Control |

|

After the publication of works

such as “Silent Spring” (Carson, 1962), public awareness of the dangers

associated with insecticides are increasingly changing the way we treat

our environment, and the way we institute environmental controls.

Consequently, efforts to introduce more environmentally friendly methods

of vector control, such as the use of traps without insecticides,

challenges us to understand more about the vectors that transmit the

disease, as well as the ecological balance that we - as humans - strike

with them.

We live in a world where various

technical means of control are available to address the spread of the

disease. However, sleeping sickness is a disease of the developing

world, where despite the multitude of control strategies, the issues

have widely been neglected and abandoned. One of the key components

required to bring about effective change is to consider the

sustainability of the control strategy, and to encourage local

communities to take ownership over the process, thereby empowering

people to take an active role in an environmentally conscious solution.

Increasing knowledge through culturally sensitive education, providing

technical support, and a long-term commitment of basic resources to

beneficiary communities is essential for large-scale tsetse control

(Swynnerton, 1925).

Alongside efforts to reduce the

spread of disease through environmental controls, there is also an

urgent need to improve current surveillance and diagnostic procedures.

Mortality can be drastically reduced when cases can be diagnosed early

enough to prevent the progression of late-stage sleeping sickness.

Training and resources are desperately needed in endemic areas for

proper diagnostics and sero-surveillance.

|

| |

Perhaps the most mysterious

aspect of this disease relates to the issue of treatment options, and

the availability of drugs in Africa . Drug and vaccine development for

diseases in developing countries have always been lagging, and

unfortunately, trypanocidal drugs are no exception. An estimated 300,000

– 500,000 people are currently infected and suffering from the disease

with no hope for treatment. In 2000, the USFDA approved the use of

eflornithine by the Bristol-Myers Squibb Company and The Gillette

Company in a product called Vaniqa TM,

a topical eflornithine HCl cream to remove facial hair. Perhaps some of

the profits generated from the sale of this form of the drug will be

used to underwrite the free use of the drug in Africa, similar to what

has already happened at Merck, who donates invermectin for the treatment

of river blindness, and at Pfizer Inc for their azithormycin give away

program for the treatment of trachoma.

Atkins J. (1978) Sleeping Sickness. Tropical Medicine and Parasitology, Classic Investigations. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, New York, 181-182

Baker J.R. (1974) Epidemiology of African sleeping sickness. Trypanosomiasis and Leishmaniasis with Special Reference to Chagas Disease. CIBA Foundation Symposium, 29-50.

Baldry D.A.T. (1980) Loca

distribution and ecology of Glossina palpalis and G. tachinoides in

forest foci of west African human trypanosomiasis, with special

reference to associations between peri-domestic tsetse and their hosts. Insect Science and its Application, 1, 85-93.

Barret J.C. (1997) Control strategies for African trypanosomiases: their sustainability and effectiveness. Trypanosomiasis and Leishmaniasis. CAB International, Wallingford, 347-362.

Bouteille B. et al. (2003) Treatment perspective for human African trypanosomiasis. Fundamental & Clinical Pharmacology, 17, 171-181.

Brady J. (1972) The visual

responsiveness of the tsetse fly Glossina morsitans Westwood

(Glossinidae) to moving objects: the effects of hunger, sex, host odor

and stimulus characteristics. Bulletin of Entomological Research, 62, 257-279.

Brady J., Crump A.J. (1978) The control of circadian activity rhythms in tsetse flies: environment or physiological clock? Physiological Entomology, 3, 177-190.

Cattand P. (1994) World Health Organization Press Release. WHO/73, 7 October 1994.

Dransfield R.D. et al. (1990)

Control of tsetse fly (DipteraL Glossinidae) populations using traps at

Nguruman, south-west Kenya . Bulletin of Entomological Research, 80, 265-276.

Dumas M., Bisser S. (1999) Clinical aspects of human African trypanosomiasis (Ch. 13), Progress in human African rypanosomiasis, sleeping sickness . Springer-Verlag, Paris, 215-233.

Edeghere H. et al. (1989) Human African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness): new endemic foci in Bendel state, Nigeria . Tropical Medicine and Parasitology, 40, 16-20.

Ford J. (1960) The influence of tsetse flies on the distribution of African cattle. Proceedings of the 1 st Federal Scientific Congress, Salisbury, 357-365

Gibson W.C. et al. (1978) The

identification of Trypanosoma brucei gambiense in Liberian pigs and dogs

by isoenzymes and by resistance to human plasma. Tropenmedizin und Parasitologie, 29, 335-345.

Glasgow J.P. (1963) The distribution and abundance of tsetse. International Series of Monographs on Pure and Applied Bioology, 20, Pergamon Press, Oxford, 241.

Hargrove J.W. (1981) Tsetse: the limits to population growth. Medical and Veterinary Entomology, 2, 203-217.

Harley J.M.B., Pilson R.D. (1961)

An experiment in the use of discriminative clearing for the control of

Glossina morsitans westwood in Ankole, Uganda . Bulletin of Entomological Research, 52, 561-576.

Hendrickx G., Napala, A. (1997)

Le contròle de la trypanosome ‘á la carte': une approche intègrèe basèe

sur un Système d'Information Gèographique. Acadèmie Royale des Sciences d'Outhre Mer. Mèmoires Classe Sciences Naturelles and Mèdicales. In 8 th Nouvelle Sèrie, Tome24-2, Bruxelles, 1997, 100.

Jackson C.H.N. (1950) Pairing of Glossina morsitans Westwood with G. swynnertoni Austen (Diptera). Proceedings of the Royal Entomological Society of London (A), 25, 106.

Jaenson T.G.T. (1980) Mating behavior of females of Glossina pallidipes. Bulletin of Entomological Research, 70, 49-60.

Jahnke H.E. (1982) Livestock Production Systems in Livestock Development in Tropical Africa . Kieler Wissenschaftsverlag Vauk, Kiel, FRG.

Jordan A.M. (1974) Recent

developments in the ecology and methods of control of tsetse flies

(Glossina spp.) (Diptera, Glossinidae) – a review. Bulletin of Entomological Research, 63, 361-399.

Jordan A.M. (1976) Tsetse flies as vectors of trypanosomes. Veterinary Parsitology, 2, 143-152.

Jordan A.M. (1986) Trypanosomiasis Control and African Rural Development. Longman, London .

Kazadi J.M.L. et al., (1991)

Etude de la capacitè vectorielle de Glossina palpalis gambiensis

(Bobo-Dioulasso) vis-á-vis de Trypanosoma brucei brucei EATRO 1125. Revue d'Élevage et de Mèdecine Vètèrinaire des Pays Tropicaux, 44, 437-442.

Knudsen A.B., Slooff R. (1992) Vector-borne disease problems in rapid urbanization: New approaches to vector control. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 70, 1-6.

Kuzoe F.A.S et al. (1985)

Observations on an apparent population extension of Glossina tachinoides

Westwood in southern Ivory Coast . Insect Science and its Application, 6, 55-58.

Leak S.G.A. (1999) Tsetse Biology and Ecology, CABI publishing, New York .

Le Ray D. (1989) Vector susceptibility to African trypanosomes. Annales de la Société Belge de Médecine Tropicale, 69, Supplément 1, 167-171

Maudlin I. et al. (1990) The

relationship between Rickettsia-like organisms and trypanosome

infections in natural populations of tsetse in Liberia . Tropical Medicine and Parasitology, 421, 265-267.

McKelvey J. J. (1973) Man Against Tsetse: Struggle for Africa . Cornell University Press, Ithaca and London .

Mehlitz D. et al. (1982)

Epidemiological studies on the animal reservoir of Gambiense sleeping

sickness. Part III. Characterization of Trypanozoon stocks by isoenzymes

and sensitivity to human serum. Tropenmedizin und Parasitologie, 33, 113-118.

Mihok S. et al. Trypanosome

infection rates in tsetse flies (Diptera: Glossinidae) and cattle during

control operations in the Kagera river in Rwanda . Bulletin of Entomological Research. 82, 361-367.

Moloo S.K. (1993) The distribution of Glossina species in Africa nd their natural hosts. Insect Science and its Application, 14, 511-527.

Molyneaux D.H. (1980) Host-trypanosome interactions in Glossina. Insect Science and its Application, 1, 39-46.

Molyneux D.H., Ashford R.W. (1983) The Biology of Trypanosoma and Leishmania, Parasite of Man and Domestic Animals. Taylor and Francis, London .

Morris K.R.S. (1949) Planning the control of sleeping sickness. Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene, 43, 165-198.

Nash T.A.M., Page W.A. (1953) On the ecology of Glossina palpalis in northern Nigeria . Transactions of the Royal Entomological Society of London, 104, 71-170.

Noireau F. et al. (1989) The epidemiological importance of the animal reservoir of Trypanosoma brucei gambiense in the Congo . Tropical Medicine and Parasitology, 40, 9-11.

Rogers D.J. (1979) Tsetse population dynamics and distribution. A new analytical approach. Journal of Animal Ecology, 48, 825-849.

Rogers D.J., Randolph S.E. (1985) Population ecology of tsetse. Annual Review of Entomology, 30, 197-216.

Swynnerton C.F.M. (1925) The tsetse fly problem in the Nzega sub-district Tanganyika Territory . Bulletin of Entomological Research, 16, 99-110.

Teesdale C. (1940) Fertilization in the tsetse fly, Glossina palpalis, in a population of low density. Journal of Animal Ecology, 9, 24-26.

Wall R., Langley P.A. (1991) From

behavior to control: The development of traps and target techniques for

tsetse fly population management. Agricultural Zoology Reviews, 4, 137-159.

Watson H.J.C. (1962) The domestic pig as a reservoir of Trypanosoma gambiense. ISCTR 9 th meeting, Conakry, 327.

Weidhaas D.E., Haile D.G. (1978) The domestic pig as a reservoir of Trypanosoma gambiense. ISTR 9 th meetings. Conakry, 327.

WHO (1995) Planning Overview of Tropical Diseases Control. Division of Tropical Diseases. World Health Organization, Geneva .

Williamse L.P.M, Takken W. (1994) Odor-inducedhost location in tsetse flies (Diptera: Glossinidae). Journal of Medical Entomology, 31, 774-794.

TRYPANOSOMIASIS - SOUTH AFRICA EX MALAWI (KASUNGU NATIONAL PARK)

A ProMED-mail post

Date: Sat, 24 Dec 2005

From: Lucille Blumberg <lucilleb@nicd.ac.za>

2 cases of East African trypanosomiasis were

confirmed in Johannesburg, South Africa in the last month. Both

patients most likely acquired the disease in the Kasungu National Park,

Malawi. The 1st was a British soldier who took part in a

field exercise in Malawi. The 2nd was a South African tourist who was

on a trans-Africa overland safari. Both patients noticed large, single

erythematous skin lesions (in the groin and on the foot,

respectively) while in the Kasungu National Park and reported numerous

tsetse fly bites. Both patients visited the park within a 2-week

period in the middle of November 2005. The British soldier presented a

week after the tsetse fly bite with fever and multi-organ failure. He

had renal failure, thrombocytopenia, raised liver enzymes, and

evidence of possible cardiac involvement with a bradycardia and

features suggestive of Wenkebach-type [atrioventricular] heart block.

The 2nd patient presented about 10 days after being bitten with fever

and drowsiness and was investigated as possible malaria.

In both cases the diagnosis was confirmed in the

laboratory on blood smear examination. Both patients responded

well to suramin. The South African tourist, although clinically well,

is still being followed up to exclude central nervous system

involvement.

Dr Lucille Blumberg and Prof John Frean,

Epidemiology and Parasitology Reference Units National Institute for

Communicable Diseases Johannesburg, South Africa NICD, No 1

Modderfontein Road, Sandringham, Johannesburg <lucilleb@nicd.ac.za>

Trypanosomiasis has been emerging in Central

Africa over the past decade, but this is the 1st time that ProMED has

had a report of cases which definitely were infected in Malawi. There

are 8 human trypanosomiasis-affected districts out of the 25 districts

in Malawi: Rumphi in the northern region; Kasungu, Ntchisi, and

Nhotakota in the central region; and Mangochi, Machinga, Chikwawa, and

Mulanje in the southern region. The awareness level regarding human

trypanosomiasis is very low among both health workers and the

community (source: <http://www.fao.org/paat/html/mwi.htm>).

The local reactions at the site of tsetse fly bites are characteristic of Trypanosoma brucei rhodesiense and are associated

with regional lymphadenopathy. Early treatment

is life-saving, and trypanosomiasis should be considered in

differential diagnosis in

travellers from Malawi. Data on indigenous cases will be greatly appreciated. - Mod.EP]

see also:

Trypanosomiasis - Uganda (Kaberamaido)(02): background 20050829.2552

Trypanosomiasis - USA ex Tanzania (Serengeti): RFI 20050713.1989

2001

Trypanosomiasis - Europe ex Tanzania (05) 20010624.1197

Trypanosomiasis - Europe ex Tanzania (04) 20010618.1169

Trypanosomiasis - Kenya 20010511.0912

Trypanosomiasis - Uganda (02) 20010421.0781

2000

Trypanosomiasis, African - Australia ex Tanzania 20001107.1943

Trypanosomiasis, African: emerging (02) 20000816.1363

Trypanosomiasis, African: emerging 20000808.1320

1998

Trypanosomiasis - Uganda 19980508.0899]

[Back To Top] |

|